Status: Up to date as at 2 November 2025 Who is this for? Anyone representing themselves in a dispute who needs to keep their legal strategy, communications, and evidence-gathering confidential—and avoid handing the other side an easy win through careless emails or sharing.

What the Law Actually Says

- Privilege is a fundamental right, not a courtesy. Courts guard it jealously. Statutes only override it with clear words or necessary implication. Don’t volunteer what the law wouldn’t force you to give.

- Dominant purpose governs both pillars:

- LP for investigations: Properly framed internal fact-finding, done when litigation is realistically in prospect, can be covered. The Court of Appeal has corrected earlier, narrower approaches.

- Non-lawyers ≠ LAP: The Supreme Court has refused to extend LAP to accountants’ legal or tax advice. If you want LAP, route advice through a qualified lawyer.

- Regulators & privilege: Even powerful regulators can’t override privilege without clear statutory words. FOIA s42 and EIR 12(5)(b) both recognise LPP, with a strong public interest in maintaining it.

- Shareholder “rights” to company legal advice? No longer. The Privy Council has abolished the shareholder rule—expect tighter corporate resistance to disclosure requests dressed up as “shareholder rights”.

Systemic Weaknesses and Traps for LiPs

Where the system fails you:

- Email culture: “Reply-all” and “cc the lawyer” habits create discoverable threads with a single legal line tacked on. The law looks at purpose and audience, not your subject line.

- Attachment myths: Blanket privilege claims over whole email chains with mixed content don’t work. Courts and regulators will peel off non-privileged attachments.

- Regulatory pressure: Letters fishing for “voluntary” cooperation may sound neutral, but privilege stands unless Parliament says otherwise.

Common LiP mistakes (fix these today):

- Mixing operational chat with legal advice. Separate them—one email, one purpose.

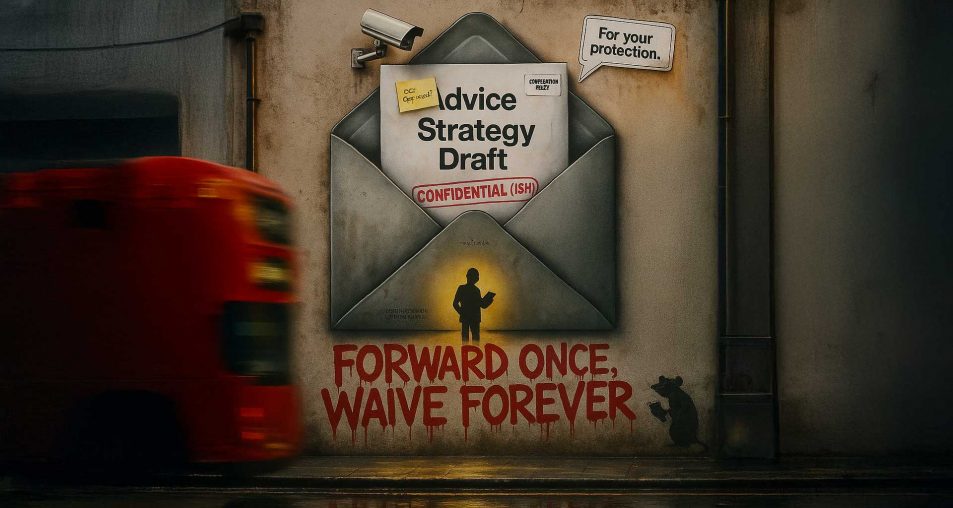

- Forwarding legal advice widely (friends, HR, advisers). That can waive privilege.

- Assuming “privileged & confidential” labels create privilege. They don’t; they only support a claim that already exists.

- DIY investigations before litigation is “reasonably in prospect.” Premature fact-gathering often sits outside LP. Get a lawyer to direct it if you can.

The LiP Playbook: Do This, Not That

- Define your “client” from day one. If you’re a director or trustee, record who is authorised to seek/receive legal advice. Keep the circle tight.

- Keep legal advice communications clean.

- Split legal from business. If you must update non-lawyers, send a separate, non-privileged note stripped of lawyer commentary. Don’t forward your lawyer’s email.

- Treat attachments as radioactive. Is the attachment privileged in its own right? If not, don’t assume the wrapper saves it.

- For investigations: As soon as litigation is realistically in view, get a lawyer to direct interviews, memos, and expert instructions. That routing helps LP.

- FOI/EIR & regulators: If you receive a request or regulatory demand touching advice, record that the information is privileged and cite FOIA s42 or EIR 12(5)(b). Weigh public interest if required; there is an inherent public interest in maintaining LPP.

- Don’t rely on non-lawyer advisers for LAP. If you need accountant or consultant input, decide whether you need the legal frame first—and route via your lawyer where appropriate.

- Guard against waiver (express and implied). Quoting or summarising legal advice in open correspondence can waive it. If you need to rely on the effect of advice, speak to your lawyer about limited or collateral waiver strategies.

- Remember the iniquity exception. Privilege will not protect communications furthering crime, fraud, or iniquity. Don’t dress wrongdoing in legal letterhead.

- Keep a privilege log. For anything you withhold, note date, author, recipients, type (LAP/LP), and the high-level purpose. Enough to justify, not enough to reveal.

Worked Examples

A. Privileged request for advice (good): Subject: Privileged – Request for legal advice: post-dismissal confidentiality To: [Solicitor] “I seek your legal advice on whether clause 7 of my compromise agreement prevents me from providing evidence to the ICO. Facts: [bullet points]. Questions: [numbered].” (Single purpose, lawyer-only; clearly framed for legal advice.)

B. Multi-recipient spaghetti (bad): Subject: Project X – all views please (cc: Legal) “Thoughts on staff rota and, [Lawyer], any legal risks?” (Mixed audiences/purposes = weak privilege claim.)

C. FOI/EIR response (public body or counterpart): “The requested material comprises confidential lawyer–client communications created for the dominant purpose of legal advice/litigation. We rely on FOIA s42/EIR 12(5)(b). We have considered the public interest and, given the strong public interest in preserving LPP, the balance favours maintaining the exemption.”

Fresh Developments (Late 2024/2025)

- Shareholder access to company legal advice: The Privy Council has abolished the shareholder rule ( Jardine Strategic v Oasis [2025] UKPC 34 ). Expect tighter corporate resistance to disclosure requests from shareholders.

- Privilege with regulators reaffirmed: The Sports Direct v FRC [2020] EWCA Civ 177 line of cases remains the reference point: privilege stands unless Parliament says otherwise—and attachments don’t automatically get a free ride.

- Dominant purpose remains king: The Jet2.com Ltd v CAA [2020] EWCA Civ 35 guidance on multi-addressee emails still applies; in-house lawyers wearing business hats are not a magic shield.

Red Flags: Stop and Rethink If You See These

- “We’ll just cc Legal.”

- “Let’s send the whole chain and all attachments under a ‘privileged’ banner.”

- “The regulator only asked nicely.” (Privilege doesn’t vanish because a letter sounds polite.)

- “Our accountants said…” (Fine advice; not LAP.)

Quick Checklist Before You Hit Send

- Audience: Only lawyer + authorised client group?

- Purpose: Is the dominant aim legal advice or litigation? If mixed, split it.

- Attachments: Do they independently qualify? If not, don’t attach—describe instead.

- Labels: Add them (they help), but don’t rely on them.

- Record: Keep a short note of when litigation became a real prospect; it can matter for LP.

Sources & Authorities

- Dominant purpose / multi-recipient emails: R (Jet2.com Ltd) v CAA [2020] EWCA Civ 35

- Litigation privilege in investigations: SFO v ENRC [2018] EWCA Civ 2006

- Non-lawyer advice not covered by LAP: Prudential [2013] UKSC 1

- Regulators can’t displace LPP without clear words: Sports Direct v FRC [2020] EWCA Civ 177 ; ICO FOIA/EIR guidance

- “Shareholder rule” abolished: Jardine Strategic v Oasis [2025] UKPC 34

Bottom Line

Privilege is powerful only if you treat it as a rule of evidence, not office folklore. Write less, separate purposes, keep the circle small, and route the right work through the right people at the right time. Do that, and you keep your strategy yours. Fail, and you risk handing your playbook to the other side.

This guide is for information only and does not constitute legal advice. If in doubt, consult a qualified solicitor before sharing sensitive material.